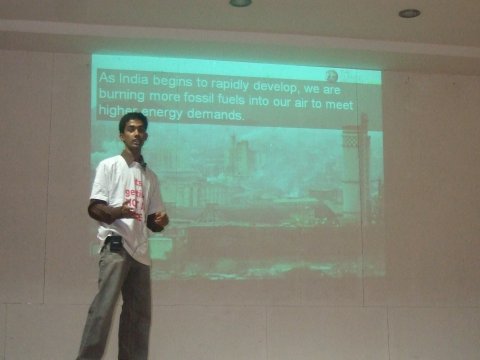

Ravi Theja Muthu conducting a climate change awareness camp for rural

students in the district of Andhra Pradesh in India

BY RASHMI VASUDEVA

Meet a passionate youngster, a member of a growing network of twenty-somethings in India, who are convinced about the dangers of climate change and who want to convince young India about it.

I had arrived early for the interview scheduled at a popular café, the hangout for Bangalore's hip, carefree youngsters. I thought I was meeting one of this breed and assumed this was the ideal place for a chat.

He walked in, a gangly lad wearing a T-shirt that had ‘Say no to pollution' blazing right across. His laptop was in a jute bag and I should have been forewarned then.

I smilingly handed him the coffee menu, only to be told that I should help myself since he does not believe in eating or drinking ‘global food'.

Before I could react, he leaned forward and recited how many food miles that Brazilian coffee I was eyeing would have traversed. Thoroughly chastised, I asked the waiter for the local version of the cappuccino in a whisper.

Shining zeal but…

Ravi Theja Muthu's idealism might be naïve but his earnestness comes shining through. If he is to be believed, all his friends and members of the year-old Indian Youth Climate Network (IYCN), a growing network of youngsters who are convinced about the dangers of climate change and who want to convince young India about it, are equally sincere and gung-ho about their cause.

IYCN is the brainchild of Kartikeya Singh, a graduate in ecology and sustainable development. “Kartikeya was the sole Indian in the 22-member US youth delegation to the 2007 UN Climate Change conference in Bali and he was aghast that he was the only youngster representing India. That spurred him to start this organization,” narrates Ravi who is studying engineering in a Bangalore college.

Spreading the word

What began as a small effort to spread awareness about climate change has today blossomed into a nationwide organization with over 700 members, a strong online presence, chapters in every major state of India and partnerships with several schools, NGOs and green organizations.

Any enthusiastic youngster willing to give some time to “spreading the word” is welcome to join.

What about the funds, I ask. “If it is a big project, funds are easy to come. But when it is educating kids in a rural school or convincing busy college students to begin a tree planting programme, money often dries up. Many times, I end up using my pocket money and so do others,” he shrugs.

Cycling + bus + walking

In Bangalore, ICYN has around 25 members, all of whom are encouraged to adopt the mantra of ‘Cy-ba-na' -- Cycling + bus + Nadiyodu (walking) for all their commuting. Ravi is a strict follower and admits he constantly pesters others, including his folks, to do so.

And he, of course, does not eat or drink ‘global food' –any food that has travelled miles to reach your plate.

But wouldn't this ideology reflect in the message climate change warriors like Ravi are trying to spread? If it does, would it not sound impractical and put off some of the people he's communicating with about climate change?

Doing more harm than good?

Worryingly, are these well-meaning youngsters doing more harm than good by making it all look rather untenable? What happens when there is a dire necessity for food imports? Will we calculate food miles then?

Ravi is too young and too caught up in describing his activities to either answer or raise such questions.

So I ask him about the reaction of the youngsters to whom he preaches these practices. How does he hope to convince the aspirational youngster on the road, with money jingling in his pockets and eyes full of materialistic dreams to not step into that pizza outlet with his date?

“I explain to them in detail about how the ingredients for their slice of pizza travel from so many different parts of the world and how it all ultimately adds up.”

Does he think such an explanation will hold water? He admits that his young audience is usually very charged up by the end of his workshops but the effect tends to peter away once they return to their classes and their routine.

“What I have noticed is rural kids are more willing to implement such practices. Perhaps because they are seeing the effects of global warming first hand…with the rains erratic, droughts becoming annual affairs and crops failing regularly,” he says gravely.

Roping the parents in

Ravi is justifiably proud of his efforts to teach rural students in the state of Andhra Pradesh (AP), one of India's largest and most-drought-affected states.

“We were overwhelmed in the village of Chittoor where not just the kids but also their farmer parents listened to us with rapt attention.”

He held awareness sessions for Chittoor farmers about the benefits of seed diversity and crop rotation – practices that have been forgotten thanks to the rapidly changing agricultural landscape in India where increasingly, farmers only want to grow commercial crops.

“Actually, ancient Indian practices have always been sustainable and eco-

friendly. We tell people to simply listen to their grandfathers,” he says, with a touch of solemnity unusual in a youngster like him.

The thin green line

Here again, the question arises about where to draw the line. Does fighting against global warming also involve resisting globalization?

For, it is globalization that has introduced these farmers to profitable crops and growing such crops is indeed signalling the end of seed diversity and crop rotation. But how will you convince these bone-poor farmers not to make profits?

Are then activists like Ravi complicating issues by giving a simplistic spin to climate change?

“We only concentrate on telling people about the simple changes they can make – saying no to plastic, switching off electrical appliances, disposing garbage with care and the like. We don't complicate anything,” he says in ardent seriousness.

“I know everybody won't listen to me. But some might. These are easy practices to follow. I hope they at least adopt these if giving up pizza and latte are too difficult,” he adds, looking straight at me.

I nod in fervent agreement.

Rashmi Vasudeva is a mid-career journalist currently on a two-year sabbatical after a nine-year stint in a daily newspaper ‘Deccan Herald' in Bangalore, India. She writes on a wide variety of topics including social issues, fashion, food, climate, art and culture. When she quit, she was heading the lifestyle section of the newspaper. The sabbatical is to pursue the Erasmus Mundus Masters in Media and Globalisation in Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK and she hopes to graduate in 2011 specializing in war and conflict. She continues to freelance and also blogs regularly at